& the Subtle Virtuosity behind it

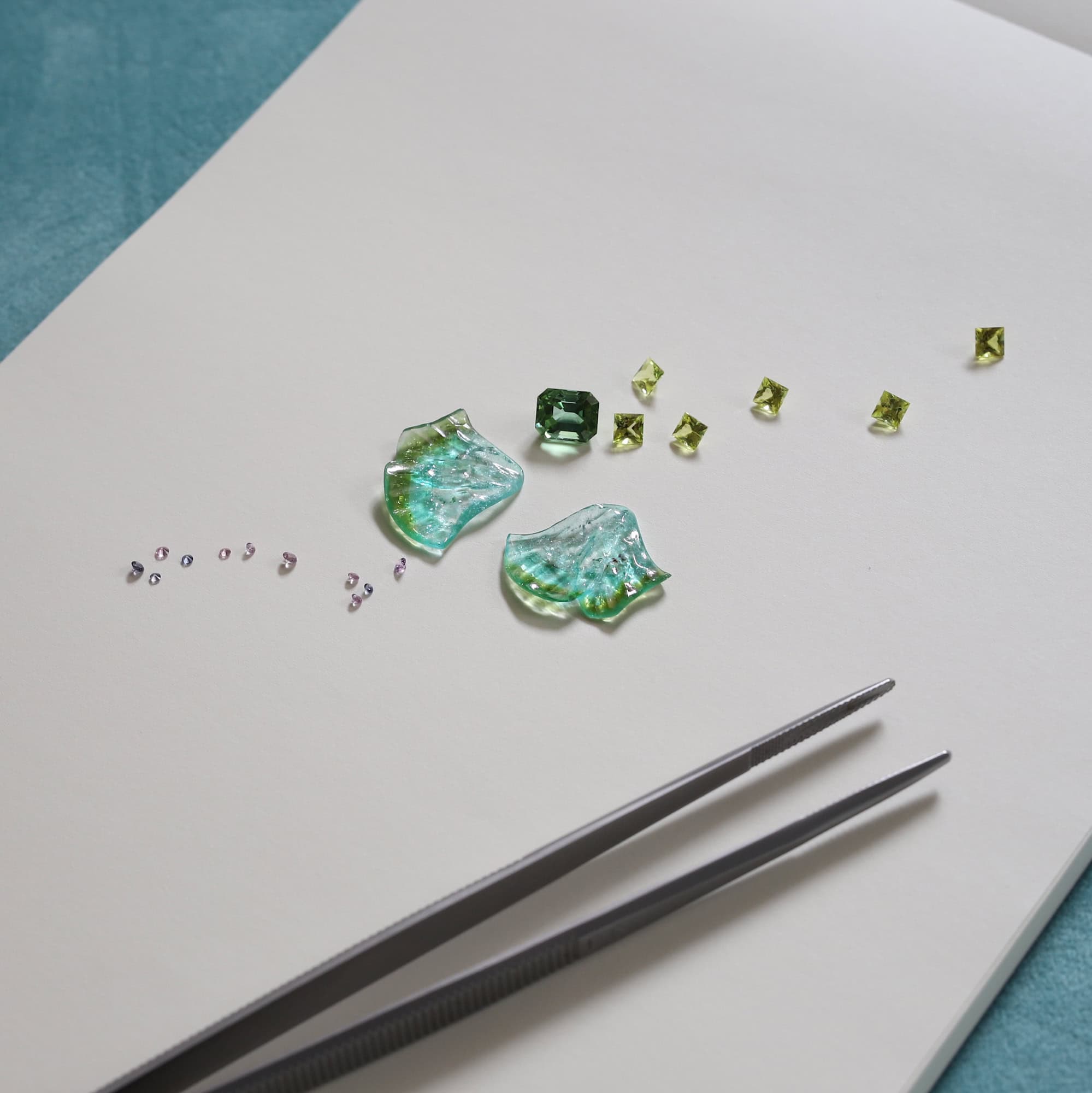

The term itself may sound uncomplicated, but carving a gemstone isn’t simple. The ethereal looking paraíba tourmaline shell-shaped ring is a case in point. The incredible detail in each little crease makes the whole piece that much more sumptuous.

Gem cutters have engraved minerals with figures or inscriptions from the earliest days, when they were considered an utmost luxury. Relief carvings, the proper term for designs that get projected out of the stone, were specially admired in ancient Greece as they were thought to be generally more impressive than intaglio images, which are cut into the stone. Egyptians, Romans and Persians also favoured these ornamental accessories, but due to status, they were most likely worn by members of the nobility and royalty than the masses.

The contemporary process of this technique remains basically the same as it was in antiquity, albeit for the use of somewhat more sophisticated instruments. It all begins with the gem selection and then cutting to the shape of choice. Though the end product does need to be moderately larger than it would otherwise to allow enough room for the carving process to take place.

In old times, artisans depended on basic tools, but nowadays, modern jewellers use electric drills for the initial stage of hollowing out of the gem rough. Fun fact: for particular procedure reasons, the said drill is plunged into a mixture of oil and some sort of abrasive powder. Oftentimes, diamond dust is the go-to element!

Three main criteria are used by gemologists to evaluate carvings: material, workmanship, and artistry. Naturally, scale is also factored in, though that’s weighted in a slightly different manner. Save scarce exceptions, labour is what drastically dictates the value. The larger the piece and the greater the detail: consequently, more time and effort were involved. So, unless we are talking about, say a super transparent paraíba or emerald perhaps, the material worth will be secondary to the work entailed.

As fine jewellers, we are extra meticulous about finding the proper resources to work with. So, while lapidaries may create carvings out of many minerals, we exclusively opt for those cut from hard and/or transparent materials. These are overall higher in quality and value than those made out of softer substances.

As a rule, the “base matter” for carvings should be free from flaws, such as fractures and evident surface level inclusions. The end result will rarer and more valuable if it exhibits fine colours and lacks blemishes.

It’s perfectly fair to state that the line between art and jewellery has always been blurred. And this specific procedure is a perfect example of how the two worlds collide.

Be it geometrical or abstract, some sort of natural-world depiction or mystical element, these artworks made from colourful crystals are a remarkable way of infusing complexity into ornaments.

Our love for artistically carved gemstones likely originates from the same root as that for “customisation” as a whole: even if they come from a collection where the designs are similar, there are incremental differences between each handcrafted piece, so you are always guaranteed a very human quality to your piece.

To sum it up, this labour intensive ancient art form requires great artisanal skill, and when expertly done, it adds a whole new level of sculptural intricacy to jewellery.